![]() Número 24, julio, 2024: 69–78

Número 24, julio, 2024: 69–78

ISSN versión impresa: 2071–9841 ISSN versión en línea: 2079–0139 https://doi.org/10.33800/nc.vi24.359

Nota científica

NEW QUATERNARY FOSSILS FROM HIGH ELEVATION CAVE DEPOSITS IN CUBA

Nuevos fósiles del Cuaternario colectados en depósitos cavernarios a alta elevación en Cuba

Lázaro W. Viñola-López1,2*, Osvaldo Jiménez-Vázquez3, Abel Hernández Muñoz4,

Carlos R. Borges-Sellén5a, Alberto F. Arano-Ruiz5b and Jesús Paz Castro6

1Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611, USA.

2Department of Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611, USA.

3Gabinete de Arqueología, Oficina del Historiador de La Habana, Cuba. osvaldojimenez@patrimonio.ohc.cu, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2281-5676.

4Fundación Antonio Núñez Jiménez in Sancti Spíritus, Cuba. abel.hmrg@gmail.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4427-7189.

5Sociedad Cubana de Geología, Cienfuegos, Cuba. acarlosrafaelborgessellen@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0009-0001-2021-8774; baarano610823@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0009-0006-6949-5162.

6Museo Municipal Cumanayagua, Cienfuegos, Cuba. mariliniglesias5@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0009-0006-8128-2581.

*Corresponding author: lwvl94@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2956-6759.

[Received: February 27, 2024. Accepted: May 22, 2024]

ABSTRACT

High elevation fossil deposits in Cuba have been poorly studied, and there is a limited understanding of how altitudinal changes could have affected the composition of faunal communities in the past. Here, we report fossils of 13 vertebrate species and an invertebrate from 11 late Quaternary cave deposits at elevations ranging from 532 to 1123 meters above sea level, located in the Guamuhaya Masiff in central Cuba. The composition of the vertebrate fauna assemblages recovered from these localities resembles that known from other lowland deposits and includes eight extinct, one extirpated, and four extant species. Furthermore, the specimens reported here record the highest elevation known for nine species recovered.

Keywords: extinct vertebrates, Pico San Juan, Guamuhaya Massif, mammal, Caribbean.

RESUMEN

Los depósitos paleontológicos de cuevas a gran elevación en Cuba han sido poco estudiados y existe una comprensión limitada de cómo los cambios altitudinales pudieron afectar la composición de comunidades terrestres durante el pasado. Aquí reportamos fósiles de 13 especies de vertebrados y un invertebrado colectado en 11 depósitos paleontológicos cavernarios del Cuaternario tardío a una altura que oscila entre 532 y 1123 metros sobre el nivel del mar, ubicadas en el macizo Guamuhaya, en el centro de Cuba. La composición de la fauna de vertebrados recuperados en estas localidades se asemeja a la conocida de otros depósitos en las tierras bajas, e incluye ocho especies extintas, una extirpada y cuatro que aun habitan la región. Los especímenes reportados aquí registran la elevación más alta conocida para nueve de las especies recuperadas.

Palabras clave: vertebrados extintos, Pico San Juan, Macizo Guamuhaya, mamífero, Caribe.

Quaternary fossil-bearing deposits with vertebrate remains are relatively abundant throughout the Cuban archipelago, especially in areas of elevated karstification. In Cuba, fossils are often found in cave deposits, sinkholes, and fissures but have also been reported less often from springs and tarpits (Silva et al., 2007; Woloszyn & Silva, 1977). Most of these localities lie at low elevations above the current sea level, as most of the karst development in Cuba is located in the lowlands. Therefore, there is a limited understanding of the fauna that inhabited some of the highest mountains in Cuba during the Quaternary and how they may relate to what has been described elsewhere (Nuñez Jimenez, 1998; Silva et al., 2007). Today, these high-elevation areas are biodiversity hotspots within the island and provide habitat to many local endemic and endangered species (Gonzalez Alonso et al., 2012).

Similarly, mountain ranges on other islands in the Caribbean region are refugia for a high diversity of endemic vertebrates, some of which are local endemics and others that have a broader historical distribution but, because of habitat fragmentation, are restricted to remaining high elevation primary forest (Anadón-Irizarry et al., 2012; Hedges et al., 2018). Fossils collected in caves in the mountains of the Tiburon Peninsula in Hispaniola have preserved the co-occurrence of extinct locally endemic mammals in association with species that once had a wider distribution throughout the island in the late Quaternary and are either extinct today or have suffered from significant habitat reduction (Cooke et al., 2011; Viñola-López et al., 2022; Woods, 1989).

Figure 1. Localities in the Guamuhaya Massif in central Cuba. A) forest in the region of Pico San Juan and general areas from where several of the caves with fossils reported here are found. B) entrance of Cueva El Sedro Seco, one of the richest localities collected. C) interior of Cueva 92 Aniversario de Antonio Nuñez Jimenez with secondary formations.

Here, we report the faunal assemblage from eleven caves between 532 and 1123 meters above sea level (m) located near Pico San Juan in the Guamuhaya Massif, Municipality Cumanayagua, Cienfuegos Province in south-central Cuba (Fig. 1). The specimens from Cueva de Maguayara (532 m), Cueva de Carmen y Lito (671 m), Cueva El Almiqui (1037 m), Cueva El Cedro Seco (1023 m), Cueva de la Lechuza (763 m), Cueva Julio Cesar (1053 m), and Cueva Cimarrones 16 (991 m), Cueva 92 Aniversario de Antonio Nuñez Jimenez (1021 m), and Cueva A6 (1123 m) were collected by members of the spelunking group Samá from the Sociedad Espeleológica de Cuba between 2014 and 2018 (Hernández Muñoz et al., 2015). Fossils from Cueva de Doña Rosa (900 m) were likewise collected by members of Samá in August 2001. Fossils from Cueva de la Campana (1010 m) were collected by Roberto Castellón from the Sociedad Espeleológica de Cuba in Agosto de 1979.

The specimens are housed at the Gabinete de Arqueología, Oficina del Historiador de La Habana, the facility of the spelunking group Samá in the city of Sancti Spiritus, and the Museo Municipal de Cumanayagua, in Cienfuegos. The vertebrates identified from these localities are well-known from the late Quaternary fossil record of Cuba, and their identification was based on characters described in the literature (Aranda et al., 2015; Jiménez-Vázquez et al., 2005; Olson, 1974; Silva et al., 2007) and comparison with specimens available in the collections at the Instituto de Ecologia y Sistematica, and the Gabinete de Archeologia de la Oficina del Historiador de la Habana in Havana, Cuba. Radiometric dates are not available for any of the localities reported here, but considering the faunal association,

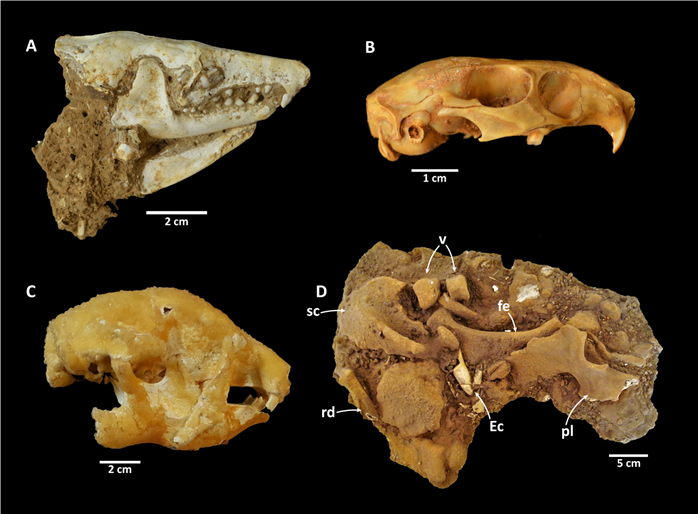

Figure 2. Selection of fossils recovered from several caves in the Guamuhaya Massif. A) Skull and associated mandibles of Atopogale cubana collected in Cueva El Almiqui; B) skull of subadult specimens of Boromys offella collected in Cueva El Sedro Seco; C) skull with associated mandible of Neocnus gliriformis collected in Cueva 92 Aniversario de Antonio Nuñez Jimenez; D) partial skeleton of juvenile specimen of Megalocnus rodens recovered from Cueva de la Campana. Abbreviations: Ec, chela cf. Epiloboceras; fe, femur; pl, pelvis; rd, radius; sc, scapula; v, vertebrae.

Figure 3. Skeleton of Neocnus gliriformis partially covered by carbonates in Cueva 92 Aniversario de Antonio Nuñez Jimenez in association with a specimen of cf. Epiloboceras (see arrow).

which includes extant and recently extinct species (Table I), the fossils are likely from the late Quaternary (Orihuela et al., 2020b). The differential preservation of the specimens from different cave deposits suggests that they are likely allochronic (Fig. 2). Direct and indirect dates of the extinct species recovered from these cave deposits are available from elsewhere in Cuba and fall in the late Pleistocene-Holocene (Orihuela et al., 2020b).

Most of the species found in these caves were widespread in Cuba during the late Quaternary, and their remains have been collected from other paleontological deposits at low elevations (Jiménez-Vázquez et al., 2005; Silva et al., 2007; Suarez, 2022). Among mammals, only two of the ten species are still present in the region, and the fossils reported here represent the highest elevation on record for the extinct and extirpated species. Fossils of rodents are the most abundant in the cave deposits, and four species are identified. Two of the species (Geocapromys columbianus and Boromys offella) are extinct, but the other two (Capromys pilorides and Mysateles prehensilis) are still present in the area of Pico San Juan (Fig. 2) (Silva et al., 2007).

The four sloth species known from the late Quaternary of Cuba are present in the collection, including the more terrestrial species Mesocnus browni and Megalocnus rodens (Figs. 2 and 3). Besides the more terrestrial habits of Megalocnus rodens and Mesocnus browni and their abundance in localities with open habitats (Arredondo Antunez, 2012; Silva et al., 2007), the fossils from Cueva El Amiquí, Cueva Cedro Seco, and Cueva de la Campana show that they additionally inhabited mountain forests and likely used a wide range of ecosystems through the altitudinal gradient. This is further supported by the discovery of remains of Mesocnus browni and Megalocnus rodens inside caves and sinkholes in mogotes and hills at intermediate elevations near the 200 m in western and central Cuba (Condis Fernandez, 2010; Nuñez Jimenez, 1998; Silva et al., 2007). Three partial skeletons of sloth corresponding to two species were found in Guamuhaya Massif, but most of the fossils reported correspond to isolated bones. A partial skeleton of Megalocnus rodens was collected from Cueva de la Campana (1010 m), (Fig. 2), and two skeletons of Neocnus gliriformis (a subadult and an adult) were found in Cueva 92 Aniversario de Antonio Nuñez Jimenez (1021 m) (Figs. 2 and 3). Explanations for how these specimens were deposited into the cave include that they could have been transported during a storm, may have fallen inside the cave and become trapped, or perhaps utilized the cave as a refugium typical of some mainland species (e.g., Hunt & Lucas, 2018; Thompson et al., 1980). Partial and complete skeletons of sloths have been found in multiple cave and sinkhole deposits in Cuba, but taphonomy studies about the origin of those specimens are lacking.

The eulipotyphlans Nesophontes micrus and Atopogale cubana were widely distributed throughout Cuba until the late Holocene. The former survived until the arrival of Europeans to Cuba and is abundant in paleontological deposits, particularly in ancient owl roosts (MacPhee et al., 1999; Orihuela, 2023). Historical accounts indicate that A. cubana may have survived in the Guamuhaya Massif until the second half of the 19th century. However, today it is found only in the mountain forests of Pico Cristal and Alejandro de Humboldt national parks in eastern Cuba at an elevation between 400 and 800 m (Kennerley et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2007) but fossil and archaeological specimens from elsewhere on the island show that this species occupied a broader spectrum of habitats (Silva et al., 2007). The Cuban Solenodon builds tunnel systems used by family groups and is primarily nocturnal (Silva et al., 2007). In Cueva El Almiqui, a partial skeleton comprised of several vertebrae, ribs, a scapula, two mandibles, and a complete skull was collected (Fig. 2), and an additional partial skeleton was recovered in Cueva Julio Cesar. The discovery of these two individuals of A. cubana, as well as partial skeletons of the extinct A. arredondoi inside other caverns in western Cuba, suggest that the species Atopogale may have frequented inside caves or were accidentally trapped inside them (Condis Fernandez, 2011).

The frog Osteopilus septentrionalis is widespread throughout the island today and is found in a broad range of habitats. Fossils referred to this species have been collected primarily in central and western Cuba (Aranda et al., 2017; Jiménez-Vázquez et al., 2005; Orihuela, 2010). On the other hand, 58 species of Eleutherodactylus are known in Cuba today.

Fossils of Eleutherodactylus have been reported from other quaternary deposits in central and western Cuba, and Isla de la Juventud (Aranda et al., 2020; Jiménez-Vázquez et al., 2005; Orihuela et al., 2020a), but identification beyond the generic level is difficult due to a lack of comparative anatomical studies.

One of the more interesting findings from the caves in Pico San Juan are remains of the extinct bird Nesotrochis picapicensis, which survived until the late Holocene and is common in paleontological and cultural deposits in western Cuba. Remains of this species collected in Cueva Julio César represent the easternmost and highest fossil record to date. However, there is a pendant made from a tarsometatarsus of N. picapicensis that was found in the archaic archaeological site Cueva de los Chivos, localized on the Valle Jibacoa, Guamuhaya Massif Sancti Spiritus Province, which is further east (Cordoba Medina, 2014). Nesotrochis picapicensis was initially considered to be a rail (Fischer & Stephan, 1971) but mitochondrial genome analysis of a congeneric species from Hispaniola (N. steganinos) showed that Nesotrochisis is sister to Sarothruridae and Aptornithidae from the old world (Oswald et al., 2021). The humerus of Nesotrochis shows that these birds were flightless like other endemic birds from the Caribbean islands (Olson, 1974). Remains of N. picapicensis are often found in association with other vertebrates that preferred wetlands and open habitats, like Crocodylus rhombifer, Mesocapromys nanus, M. sanfelipensis, Mustelirallus cerverai, Ferminia cerverai (Jiménez-Vázquez et al., 2005; Rojas-Consuegra et al., 2012; Suarez, 2022; Viñola-López et al., 2018). However, the presence of N. picapicensis and N. steganinos in cave deposits at high elevations in Cuba (Cueva 92 Aniversario de ANJ, 1021 m; Cueva Julio Cesar, 1053 m) and Hispaniola (Trouing Jeremie # 5, 1275 m; Touring Marassa, 1875 m; Touring Pas Konnen, 1980 m) (Oswald et al., 2021; Viñola-López et al., 2023) may suggest that these species were also forest dwellers and inhabited montane habitats. Some extant members of the family Sarothruridae, sister taxa of Nesotrochis, are found in a wide range of habitats from sea level to montane forests at 2000 m (Colyn et al., 2019l Goodman et al., 2011). The specimens of N. picapicensis from Cueva 92 Aniversario de ANJ correspond to a partially associated skeleton collected 50 meters inside the cave in association with partial skeletons of a Mysateles prehensilis and two Neocnus gliriformis. No evidence of an owl or raptor roost was found in this locality, suggesting that a predator did not transport the specimens from lower elevations.

Five species of the genus Epiloboceras are found in freshwater habitats on the island. The species E. capolongoi is known exclusively from mountain rivers and streams in the Guamuaya Massif and was recently reported from several localities at an elevation near the 1000 m in the surroundings of Pico San Juan (Rodríguez-Cabrera et al., 2023). The two fossils of crustaceans from Cueva de la Campana and Cueva A6 morphologically resemble E. capolongoi, which is the only large freshwater crustacean found in the area. Its direct association with fossils of the extinct sloths Megalocnus rodens and Neocnus gliriformis indicate that this species has been present in the Guamuaya Massif at least since the late Quaternary. However, until the specimens are studied and described in more detail, we refer the specimens to genus level

The specimens described here extend the altitudinal distribution of extinct rodents, sloths, the eulipotyphlans Nesophontes micrus and Atopogale cubana, and the flightless bird Nesotrochis picapicensis. Although these species are also known from Quaternary deposits elsewhere in Cuba, their fossils discussed here provide necessary insight regarding the fauna that once inhabited the highlands. Further exploration of these and other high elevation paleontological deposits in Cuba will help us better understand changes in faunal composition related to habitat and altitude gradients.

Table I. Fossil vertebrates found in cave deposits at high elevation near Pico San Juan in the Guamuhaya Massif in south-central Cuba. † = extinct; * = extirpated; 1 = reported by Silva et al. (2007). CEA, Cueva El Almiquí; CCS, Cueva El Cedro Seco; CJC, Cueva Julio Cesar; CL, Cueva de la Lechuza; CC16, Cueva Cimarrones 16; CC, Cueva de la Campana; CM, Cueva Mayaguara; CCL, Cueva Carmen y Lito; CANJ, Cueva 92 Aniversario de ANJ; CA6, Cueva A6; CDR, Cueva Doña Rosa.

|

Taxa |

CEA |

CCS |

CJC |

CL |

|

CC16 |

CC |

CM |

CCL |

CANJ |

CA6 |

CDR |

|

|

|

|

|

Mammalia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Atopogale cubana* |

X |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Nesophontes micrus† |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Mysateles prehensilis |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

Capromys pilorides |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Geocapromys columbianus† |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

Boromys offella† |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

Megalocnus rodens† |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

Mesocnus browni† |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Acratocnus antillensis† |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X1 |

|

Neocnus gliriformis† |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Amphibia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Osteopilus septentrionalis |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eleutherodactylus sp. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aves |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nesotrochis picapicensis† |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Crustacea |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

cf. Epiloboceras sp. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Ercilio Vento Canosa, José Manuel Ramos, and Roberto Castellón for access to the specimens reported here. This manuscript was improved thanks to the input provided by Jason R. Bourque, the editor Gabriel de los Santos, and two anonymous reviewers.

REFERENCES

Arredondo Antúnez, A. (2012). Los perezosos extintos. In R. Borroto-Paez, & C.A. Mancina (Eds.), Mamíferos en Cuba (pp. 29–37). UPC Print.

Anadón-Irizarry, V., Wege, D. C., Upgren, A., Young, R., Boom, B., León, Y. M., Arias, Y., Koenig, K., Morales, A. L., Burke, W., & Pérez-Leroux, A. (2012). Sites for priority biodiversity conservation in the Caribbean Islands Biodiversity Hotspot. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 4(8), 2806–2844.

Aranda, E., López, J. G. M., Jiménez, O., Luna, C. A., & Viñola-López, L. W. (2017). Nuevos registros fósiles de vertebrados terrestres para Las Llanadas, Sancti Spíritus, Cuba. Novitates Caribaea, (11), 115–123.

Aranda, E., Viñola-López, L. W., & Álvarez-Lajonchere, L. (2020). New insights on the Quaternary fossil record of Isla de la Juventud, Cuba. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 102, 102656.

Colyn, R. B., Campbell, A., & Smit-Robinson, H. A. (2019). Camera-trapping successfully and non-invasively reveals the presence, activity and habitat choice of the Critically Endangered hite-winged Flufftail Sarothrura ayresi in a South African high-altitude wetland. Bird Conservation International, 29(3), 463–478.

Condis Fernandez, M. (2010). Inferencias paleoecológicas sobre especies de la mastofauna cuaternaria cubana, conservadas en el depósito superficial de La Caverna Geda, Pinar del Río, Cuba. [Doctoral dissertation thesis, University of Pinar del Río and University of Alicante].

Condis Fernandez, M. (2011). Los “insectivoros” extintos. In R. Borroto-Paez, & C.A. Mancina (Eds.), Mamíferos en Cuba (pp. 38–43). UPC Print

Cooke, S. B., Rosenberger, A. L., & Turvey, S. (2011). An extinct monkey from Haiti and the origins of the Greater Antillean primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 2699–2704.

Córdova Medina, A. P. (2014). La zooarqueologia en Cueva de los Chivos, sitio protoagricultor del macizo montañoso de Guamuhaya, Manicaragua, Villa Clara [Paper presentation]. XII Conferencia Internacional de Antropología, Instituto Cubano de Antropología, La Habana, Cuba.

Fischer, K. & Stephan, B. (1971). Weitere Vogelresteaus dem Pleistozän der Pio-DomingoHöhle in Kuba. Wiss. Zeitsch. Humboldt-Univ. Berlin, Math. Nat. R., 20, 593–607.

González Alonso, H., Rodríguez Schettino, L., Rodríguez, A., Mancina, C. A., & Ramos García, I. (2012). Libro rojo de los vertebrados de Cuba. Editorial Academia

Goodman, S. M., Raherilalao, M. J., & Block, N. L. (2011). Patterns of morphological and genetic variation in the Mentocrex kioloides complex (Aves: Gruiformes: Rallidae) from Madagascar, with the description of a new species. Zootaxa, 2776(1), 49–60.

Hedges, S. B., Cohen, W. B., Timyan, J., & Yang, Z. (2018). Haiti’s biodiversity threatened by nearly complete loss of primary forest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(46), 11850–11855.

Hernández Muñoz, A., Pérez Ibarra, A.. Rodríguez Pino, O., & Rodríguez Lorenzo, A. (2015). Paleozoología de la cueva de Julio César, Pico San Juan, Macizo de Guamuhaya, Cuba [Paper presentation]. Congreso 75 Aniversario de la Sociedad Espeleológica de Cuba, Camagüey, Cuba.

Hunt, A. P., & Lucas, S. G. (2018). The record of sloth coprolites in North and South America:

implications for terminal Pleistocene extinctions. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 79, 27–298.

Jiménez-Vázquez, O. (2001). Registros ornitológicos en residuarios de dieta de los aborígenes precerámicos cubanos. Journal of Caribbean Ornithology, 14(3), 120–126.

Jiménez-Vázquez, O., Condis, M. M., & García Cancio, E. (2005). Vertebrados post-glaciales en un residuario fósil de Tyto alba Scopoli (Aves: Tytonidae) en el occidente de Cuba. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología, 9(1), 85–112.

Kennerley, R., Turvey, S. T. & Young, R. (2018). Atopogale cubana. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T20320A22327125. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T20320A22327125.en. Accessed on 11 July 2024.

MacPhee, R. D. Flemming, C., & Lunde, D. P. (1999). “Last occurrence” of the Antillean insectivore Nesophontes: New radiometric dates and their interpretation. American Museum Novitates, 3264, 1–19.

Nuñez Jimenez, A. (1998). Geología. Ediciones Mec Graphic Ltd.

Olson, S. L. (1974). A new species of Nesotrochis from Hispaniola, with notes on other fossil rails from the West Indies (Aves: Rallidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, 87(38), 439–450.

Orihuela, J. (2010). Late Holocene fauna from a cave deposit in Western Cuba: post-Columbian occurrence of the vampire bat Desmodus rotundus (Phyllostomidae: Desmodontinae). Caribbean Journal of Science, 46, 297–312.

Orihuela, J., L. Pérez Orozco, J. L. Álvarez Licourt, R. A. Viera Muñoz, & C. Santana Barani. 2020a. Late Holocene land vertebrate fauna from Cueva de los Nesofontes, Western Cuba: Stratigraphy, chronology, diversity, and paleoecology. Palaeontologia Electronica, 23(3) a57. https://doi.org/10.26879/995

Orihuela, J. (2023). Revision of the extinct island-shrews Nesophontes (Mammalia: Eulipotyphla: Nesophontidae) from Cuba. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 130, 104544.

Orihuela, J., Viñola, L. W., Jíménez-Vázquez, O., Mychajliw, A. M., de Lara, O. H., Lorenzo, L., & Soto-Centeno, J. A. (2020b). Assessing the role of humans in Greater Antillean land vertebrate extinctions: New insights from Cuba. Quaternary Science Reviews, 249, 106597.

Oswald, J. A., Terrill, R. S., Stucky, B. J., LeFebvre, M. J., Steadman, D. W., Guralnick, R. P., & Allen, J. M. (2021). Ancient DNA from the extinct Haitian cave-rail (Nesotrochis steganinos) suggests a biogeographic connection between the Caribbean and Old World. Biology Letters, 17(3), 20200760.

Rodríguez-Cabrera, T. M. (2023). New records and geographic range extension of Epilobocera capolongoi Pretzmann, 2000 (Decapoda: Brachyura: Epiloboceridae) in Cuba, with notes on its natural history and conservation. Nauplius, 31, e2023009.

Rojas-Consuegra, R., Jiménez-Vázquez, O., Condis-Fernández, M. M., & Díaz-Franco, S. (2012). Tafonomia y paleoecologia de un yacimiento paleontológico del cuaternario en la Cueva del Indio, La Habana, Cuba. Espelunca digital, 12, 1–15.

Silva, G., Suárez Duque, W. & S. Díaz Franco. (2007). Compendio de los mamíferos terrestres autóctonos de Cuba vivientes y extinguidos. Editorial Boloña.

Suárez, W. (2022). Catalogue of Cuban fossil and subfossil birds. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club, 142(1), 10–74.

Thompson, R. S., Van Devender, T. R., Martin, P. S., Foppe, T., & Long, A. (1980). Shasta ground sloth (Nothrotheriops shastense Hoffstetter) at Shelter Cave, New Mexico: environment, diet, and extinction. Quaternary Research, 14(3), 360–376.

Viñola-López, L. W., Bloch, J. I., Almonte Milán, J. N., & LeFebvre, M. J. (2022). Endemic rodents of Hispaniola: biogeography and extinction timing during the Holocene. Quaternary Science Reviews, 297, 107828.

Viñola-López, L.W., Garrido, O. H., & Bermudez, A. (2018). Notes on Mesocapromys sanfelipensis (Rodentia: Capromyidae) from Cuba. Zootaxa, 4410(1), 164–176.

Viñola-López, L.W., Almonte Milán, J. N., Luthra, A., & Bloch, J. I. (2024). New Quaternary mammals support regional endemism in western Hispaniola. Journal of mammalian evolution, 9722, 1–27.

Woloszyn, B. W., & G. Silva. (1977). Nueva especie fósil de Artibeus (Mammalia: Chiroptera) de Cuba, y tipificación preliminar de los depósitos fosilíferos cubanos contentivos de mamíferos terrestres. Poeyana, 161, 1–17.

Woods, C. A. (1989). A new capromyid rodent from Haiti: the origin, evolution, and extinction of West Indian rodents and their bearing on the origin of New World hystricognaths. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Science Series, 33(5), 59–89.

Citation: Lázaro W. Viñola-López, L. W., Jiménez-Vázquez, O., Hernández Muñoz, A., Borges-Sellén, C. R., Arano-Ruiz, A. F., & Paz Castro, J. (2024). New Quaternary fossils from high elevation cave deposits in Cuba. Novitates Caribaea, (24), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.33800/nc.vi24.359